This section is under construction. Yep. It takes a moment to translate the content. But so far… recipes, plants and rituals:

Cacao porcelana’s leaves

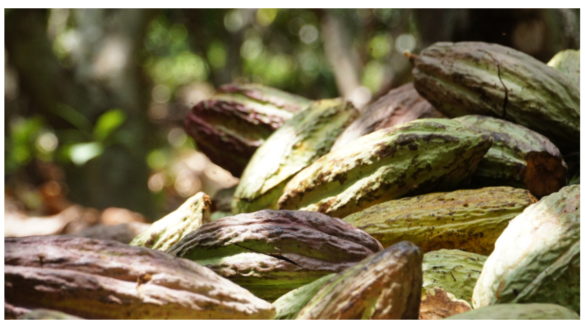

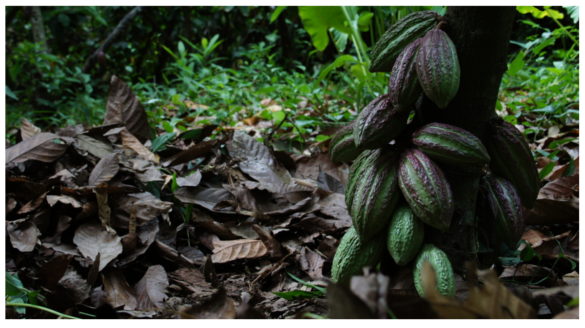

The cacao tree shown in the photo will begin producing its first fruits in eighteen months’ time. Surrounded by other cacao trees and shaded by palms, this little plant began life in July 2015, on the Diosconmigo farm, where Daniel Carei was brought up by his great-grandparents. Four hours down the mountain is Mingueo, the closest town. In this guajiro town, crossed by the main road between Santa Marta and Riohacha, APOMD (Association of Organic Producers of the Municipality of Dibulla) brings together farmers and producers who, with the support of Slow Food, hope to revive the native seed known as Porcelana cacao.

This seed originates from Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, and its natural habitat is over 200m above sea level. It grows close to water sources, protected by the shade of other trees, and its trunk can reach up to five metres in search of light. White cacao, as it is also known, has been preserved on indigenous lands. Maybe due to its delicateness and singular fermentation time, it does not attract large cacao producers in Colombia.

The majority of cacao varieties planted in this region of the country are sold to the National Chocolates Company and come from cloned seeds. They have been created in laboratories and introduced to the region by Daabon, a company known for its connection to forced displacement and the monoculture African palm plantations which extend across Magdalena and La Guajira. These clones come to farmers through technological packets that include the use of agro-chemicals and fertilizes that modify regions’ natural ecosystems. In addition to this is the damage done to biodiversity when farmers, attempting to secure the sale of their produce, only plant one type of seed.

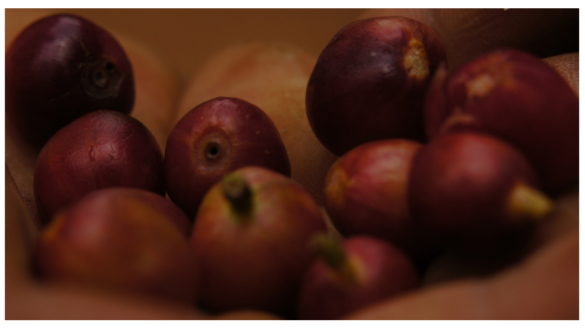

But this is only a small part of the road travelled by industrial cacao to arrive on our tables. This story is not only about a product with cloned seeds but also about a selection of beans which lacks rigour. In industrial processes which prioritise quantity over quality, varieties are mixed without qualm when they are collected. Once the beans have been fermented for several days and then dried, they are moved to the roaster without taking account of their different sizes. The small beans are burnt, the big ones are not roasted enough and thus, they are ground together to make the same paste or base. The low quality beans or husks which are thrown out during artisanal processing, are kept during industrial processing. And at this point, already far removed from the original flavor and aroma of the fruit, the uncountable preservatives and flavourings of an industry which appears generous and diverse (light chocolate, instant, vanilla flavoured, cloves and cinnamon…) are added. It is worth asking oneself how much cacao there actually is in the chocolate we are purchasing.

There are also innumerable details in the story of recuperating a seed. Let’s stop beating about the bush and come back to white cacao. Has it survived because of its lack of commercial importance to the national chocolate industry? Has it survived by being part of the diet of indigenous families who have prepared it in their houses in the middle of the Sierra for years? It is possible. Malanga, guatila, and chachafruto are other examples of native fruits that have no commercial importance, but which are nevertheless a high quality source of nutrition. What is not named is forgotten, and often it is someone from outside who makes us look inside and value what we have neglected.

More than three years have passed since APOMD and Slow Food first met in Dibulla. For Yarido Banquez, vice-president of the association, this process has not only meant the rescuing of the seed but also traditional forms of cultivation. This includes practices such as making organic fertilizer from what the surroundings provide, paying attention to the phases of the moon, varying crops and planting in triangles to protect the land, in other words: a type of agriculture which observes and applies what Nature itself has done for centuries. Beyond the difficulties caused by the lack of water caused by the El Niño phenomenon, the most difficult thing, according to Yarido, is to spread faith amongst other growers. The disappointing results of past State and private initiatives have created disbelief amongst farmers, and it is not easy to convince them to commit to a process which requires time and perseverance.

These cacao producers plant without knowing whether they will harvest any rewards, the Sierra has taught them that a lot can happen in eighteen months. For them, a clear way of building peace in Colombia is to take up the knowledge passed on from their ancestors, some of whom were Arhuaco indigenous people. Today, they are farmers who are aware of the harmful effects of the Green Revolution, and that is why they are trying to stand up to an economy which enslaves them and which generates food by poisoning the countryside. This is why they consciously choose the seed, as it represents their intention to free themselves and to free the land.

Daniel Carei, Fernando Oliveros y Yarido Banquez. Porcelana cacao producers.