Curate your life. Make it a habit. Choose what is really important to you. What gives you authentic joy, personal growth, emotional health? In this current times, personal energy reserves are essential. What does it mean to curate your life and how to do it? Guiding questions at the end of the article.

Curating your life means that your “no’s” belong to you as much as your “yes’s”. Pleasing other people is not more important than your well-being. Curating your life means really listening your self when making decisions. If you want to do something you do it, if you don’t want to, you don’t. Sacrificing your joy to please others has nothing to do with self-care.

But how do you know if you are exceeding your own boundaries? If, more than once, you have regretted going to a place when you didn’t want to. If you have felt exhausted by sharing your time with x person, and you have told yourself: Oh, I knew it! There you go! You are not respecting yourself. Yes, those are sentences I have said to myself and I have heard countless times in my astrological consultations. We grew up in a context where, due to imitation and approval seeking, we learn to listen other’s opinions even before listening our own. But well, as it is a matter of practice and repetition, we can also develop the ability to truly listen to ourselves.

Make of this simple question: “Is this really something I want to do?”, a habit.

In the same way that you strengthen a new friendship, you can strengthen the ability to listen your own intuition. Find below a few practical tips to curate your life. This Mercury retrograde and both, Taurus and Scorpio eclipses, are the perfect occasion. Cleanse and detox time. What areas of your life will you curate? It depends on where you have Scorpio in your natal chart. If you want to know more about it, click here.

Curate your personal space. Ask yourself:

Does this space reflect my inner state?

What is the meaning and function, practical and/or emotional, of the objects in here?

What am I holding on to, why, and what can I let go of?

Curate your relationships. Ask yourself about its purpose. For example:

Based on what values do I decide who is part of my personal life?

What are my social circles and based on what values am I building them?

How do I empower my friends? How do they empower me?

Curate the path to your life direction:

What are my professional goals and how are they connected to a service that goes beyond myself?

How my daily activities connect with my soul purposes?

Is what I read, write, share really aligned with my soul purpose?

Curating, as sculpting, involves revealing the soul of a thing through the simplification of its form. Why couldn’t we do the same with our lives?

Curate your life. Make it a habit from time to time. Maybe we can’t “control” who or what enters our lives, but we can decide why and for how long it stays. In the same way, we cannot “control” every thought in our mind, however, we can consciously choose which ones we get hooked on and which ones we give flight to.

.:. HOLD YOUR VISION .:. REFINE YOUR ACTIONS .:. THE ESSENTIAL WILL SHAPE YOUR PATH .:.

Words and images by Crista.

Does the So Purkh work? A friend asked me a few months ago when I told her that I had completed a quarantine with this mantra for the first time. What does it mean that it works? I asked myself. What made me recite it for forty days?

The So Purkh is a shabad in the Sikh tradition written by Guru Ram Das and a recommended practice especially for women. Among its most mentioned benefits is the manifestation of the divine masculine energy (not necessarily a divine man) in our lives. Through my personal experience I have understood that beyond my initial motivations, reciting the So Purkh opens a path of reflection regarding the importance of healing patterns in relationships

My first motivation: “Cleanse the karma of your past relationships”

Isn’t this the best “selling point”of So Purkh? Who doesn’t want to clean the karma of their past relationships? Who doesn’t want to interact without the memory of fear or pain? From the list of benefits this was for me the most attractive one. Not without surprise I discovered that end releasing a karmic relationship is only the tip of the iceberg compared to the deep cleansing process this shabad activates. Meditating with So Purkh revealed to me that it was not simply a matter of healing the wounds of a specific relationship, but to discover the patterns that I repeated in my relationships.

Perhaps these questions resonate with you: Why do I invest more energy in my relationship with others than in my relationship with myself? Why do I make creative efforts for others’ projects that I have not done for my own yet? Why do I wait for the “perfect companion” to make that journey? Why do I cook for others with a love and care that I do not show in cooking for myself? This constant waiting for “the other” is not necessarily limited to relationships with the opposite sex. Partners, colleagues, creative accomplices get into the package of “self-imposed authorities”, those people whom we unconsciously ask for permission to create.

Sharing is a pleasure, but making other people the catalyst for any kind of creation weakens self-confidence and personal power. Perhaps we make an excuse of others: if the project or the relationship doesn’t work out, we will have someone to blame. And we blame them even when they are gone. So, what about my reproaches? Are they for someone else or are they for myself? Isn’t my inner saboteur my worst enemy? Who, but me, feeds it with neglected thoughts? “That’s my real karma,” I told myself, “I need So Purkh”.

Second motivation: To attract a divine man into your life.

If you accept your desires, you accept your power. Healing your wounds by over-analysis is like learning to swim without jumping into the water. The first time I recited the mantra the effects were astonishing: the manifestation, not of one man, but two. There is no drama to tell, nor Disney ending. I attracted two mirrors that invited me to transform into me what I was criticizing in them. I asked myself which habits, relationships and thoughts were not at the service of my evolution and well-being. Questioning my routines and everything that didn’t help me build self-confidence, showed me that an unbalanced man tends to abuse the feminine, sometimes even in the form of a plant.

The So Purkh is a purge. Just as ceremonies with sacred plants do not end when you return home, your sadhana does not end when you leave the mat. In the darkness of the room and far from the neutral mind, there was only one anchor left for me: to breathe. I was not meditating for a new love, it was impossible, I just wanted peace within myself. I wanted the gift of forgiveness: to forgive myself for having remained for a long time where I could neither love, nor create. The sun rose every morning to remind me that being at peace with someone does not imply being their friend, and no matter what comes in the future, I am responsible for my projects, my dreams and my own happiness.

Three proven effects of So Purkh, based in my personal experience:

Courage over the negative voice..

I have taken action for things I wanted beyond fear of the result. I have put energy into what I want to create and see growing. I do what is on my hands honestly and without judgment. What used to be a paralyzing search for perfection and expectations has been replaced by the search for authentic connection with others as a creative intention.

Manifest and materialize…

Ideas that were waiting for me to act. Writing about So Purkh and its effects is an example. Through this article I go beyond the usual indications on how to recite it and what for. I write from my own experience, and validate my own voice.

Materialize and share.

My favorite version of So Purkh accompanies me as I write. It is another way of meditate with it: while I write, I draw or create images. To activate the masculine and feminine energies in me, is to ignite and sustain my inner fire. I feed my self-confidence, I share what I do, I stop hiding. For me that’s healing!

Written by Crista.

Have you ever wondered what your medicine is? What you came here to give and to share? The music of Almunis Alejandra Ortiz has been for many people I know, myself included, a great travel companion, particularly when I felt I had lost my way. A few days after her arrival in Barichara, which marks her return to Colombia after 17 years, I had the opportunity to sit down and talk with her.

Her sonorous fertility and lyrics invite us to ask ourselves about the root, about what nourishes and sustains us. That deep exploration, to which she herself was called when studying at the Berklee College of Music, led her to create Lulacruza, a group with which she closed a chapter in 2017, and through which she woveher connection to Latin American sounds together with a spiritual path of intense experiences. Today, through Minük, her new musical project with partner Markandeya, Almunis invites us to raise our eyes to the sky and ask ourselves about the medicine of the stars.

And amongst the stars, which are burning suns, Mirando el Fuego is born, their most recent collaboration with El Búho, a song that in my opinion embodies much of the essence of our time: the awakening of the feminine spirit that compassionately embraces the masculine, and understands that the masculine spirit also goes through the pain of reinventing itself and being born through childbirth itself. This global healing reminds us that the deeper and healthier our root is, the more we can expand and access the messages of the celestial spheres. Recognizing ourselves as channels of consciousness is the path to manifesting our own medicine.

If a woman is healed, all men are healed; if a man is healed, all women are healed. The journey of forgiving the father instead of killing him, from a symbolic perspective, demands courage. The value of not blaming the other and not seeing them as separate from me. This uncomfortable and liberating process of demolishing our own structures, questions in whose hands or in what we have placed our own healing. It is an awakening of collective consciousness that shakes even those ancestral and patriarchal traditions, which have often been healing without recognizing their own illness. It is urgent that we heal our altars, and, with love and without mercy, overthrow the “false gods” that have been wont to guide our lives.

I wonder if Almunis, like those of us who have found a cure in her music, also went through her own dark night of the soul in recent years. From her home in the mountains of her father’s land, the initial exploration and initiation of sound as a healing tool evolves towards an even more unifying perspective: that of service. Through Sonido Sana and its Embodied Voice workshops, she creates encounters for those who want to awaken their own voice as an instrument of reconnection with the purpose of life. A way of teaching singing that is not limited to vocal technique or the quest for applause. Paraphrasing Almunis: We do not express ourselves (writing, dancing, drawing, cooking, weaving…) to be loved, we express ourselves because we are love.

We teach what we most need to learn. What would you do to remember who you are and what you have come for? What would you teach while healing, and what would you heal by teaching? What would be your tool, your instrument? Or simply, as Mary Oliver, another woman indisputably connected with her creative mission, once wrote:

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what do you intend to do with your one wild and precious life?***

From left to right: Markandeya, Minük and Almunis Alejandra, in their home. Barichara, Colombia.

*** The summer day, a poem by Mary Oliver, click.

Images and text by Crista Castellanos.

The Narratives We Tell

A short interview with Usifu Jalloh, story teller from Sierra Leona.

If we understand that our lives, that we live from the time we wake up in the morning till the time we go to bed at night. That our lives are either telling a story, watching a story, listening a story or reading a story or doing a story. That’s what our lives is really all about. When you can be very aware of what your story is, your narrative, what it is, that’s when you are ready to change what you don’t like in your narrative. I’m Usifu Jalloh, otherwise some people call me The cowfoot prince, I’m a storyteller, I see myself as an architect of social change and cultural awakening.

Before I came to Colombia I told one of my best friends that I was coming to Colombia, the first thing he says: “Be careful so that they don’t kidnap you. But here I am in Colombia in the beautiful Botanical Garden, birds chirping in the air, the weathers is beautiful, with very beautiful people, it’s nice, Which narrative do we believe? You see?My country Sierra Leone went through a war narrative over 10 years and the stories told all over the world. And then we realise that we don’t like that narrative. So, we had peace.

The press tells a story, and here we go again, the press tells a story of what they want us to… or what they want to hypnotise us with. But I choose as a storyteller to tell the full story, to tell the round, complete story. Why? Because I am whole, I am complete, I am a circle, and I believe every human being is a circle, is complete. So, therefore, we have to think very carefully and be very conscious about what narratives we tell.

The key to the emotion is rhythm, is music. The key to opening the mind is emotion. Our whole body is rhythm, your heart is beating rhythmically, when your heart misses a beat you know it! I listen to the drum, as the drummer listens to the songs and the drummer watches the dances, everything is closely knit together. Every dance we do tells a story, every drumming we do tells a story, so dancing is just the physical expression of an oral narrative or let me go even further, a spiritual narrative. And dancing is just one wonderful way so we can visualise it.

Jack and the beanstalk, is a very interesting story. Who is Jack who is the giant? And this is a world wide famous story. Jack and the beanstalk When that story is told from the European point of view, the giant is the villain. But let us tell the story from the giant’s point of view. Who went in and stole the giant’s golden nuggets and so on? Who? Who went up there and stole?

So when we look at the narratives that has been told to us by the neocolonialism. We got to check that Colombia’s narrative, Argentina’s narrative, Peru’s narrative, Sierra Leona’s narrative and on and on and on, so we can really understand what are those narratives are, what are those stories, who’s point of view are we looking at?

We think many times that we are so educated. And we go into communities and we don’t respect their culture, we don´t respect their narratives, because we think we are educated. And then we go in there and then we do things and disrupt the rythm of that community, and we walk away thinking it won’t affect us, no, the shit will follow. You’re a corporate organisation you come to Colombia you build a dam and you deprive the people from their fish from their natural resources, it will come back to bite you. So whether you sell weapons to other countries to fight their wars, guess what, it will come back to bite you it will follow you and will stink behind you. It will come back to bite you.

What’s earth if it’s not the plant? What’s earth if it’s not the ant? What’s earth if it’s not you? You cannot say the leaves are beautiful and then you say the root is ugly. Those leaves, those beautiful leaves are born from that root that is under that ground. And those leaves will go nowhere if that root is not fertilised, is not fed, respected. When we talk about native Americans, how many years have they lived with nature? Thousands of years. We understand one thing: we are custodians of the earth. I strongly believe that the success of any man or woman. The success of every nation is entirely dependent on the narrative that they believe. Entirely depends on that narrative. What are you being? What are you believing?

So I love to tell stories that can challenge people to think about their own narratives. What’s your own narrative?

“The Narratives We Tell” is a short video documentary based on an audio interview with the African storyteller Usifu Jalloh, during his visit to Colombia (2015). Produced by Milo Cabieles (Nimba Danzas Africanas) and Crista Castellanos. “The Narratives We Tell” offers a glimpse at the current transition Colombia faces, from the long armed conflict to the gradual construction of a history of peace. We are the stories we tell and we have to the power to change those that confine us.

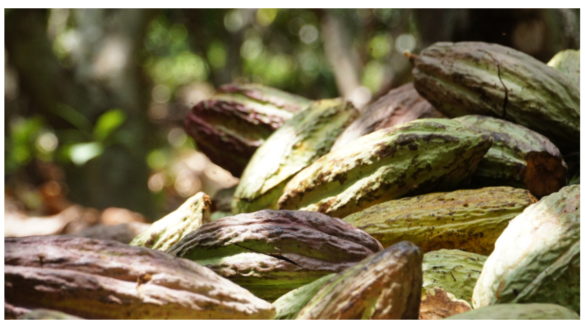

Porcelana Cacao, a native seed

Cacao porcelana’s leaves

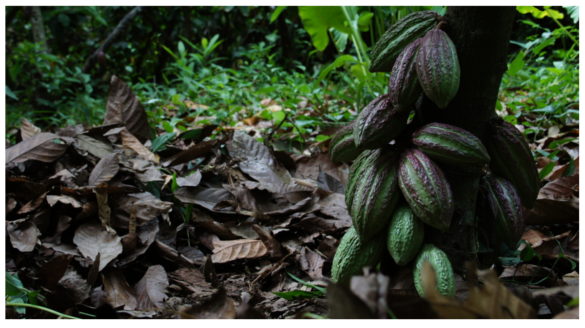

The cacao tree shown in the photo will begin producing its first fruits in eighteen months’ time. Surrounded by other cacao trees and shaded by palms, this little plant began life in July 2015, on the Diosconmigo farm, where Daniel Carei was brought up by his great-grandparents. Four hours down the mountain is Mingueo, the closest town. In this guajiro town, crossed by the main road between Santa Marta and Riohacha, APOMD (Association of Organic Producers of the Municipality of Dibulla) brings together farmers and producers who, with the support of Slow Food, hope to revive the native seed known as Porcelana cacao.

This seed originates from Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, and its natural habitat is over 200m above sea level. It grows close to water sources, protected by the shade of other trees, and its trunk can reach up to five metres in search of light. White cacao, as it is also known, has been preserved on indigenous lands. Maybe due to its delicateness and singular fermentation time, it does not attract large cacao producers in Colombia.

The majority of cacao varieties planted in this region of the country are sold to the National Chocolates Company and come from cloned seeds. They have been created in laboratories and introduced to the region by Daabon, a company known for its connection to forced displacement and the monoculture African palm plantations which extend across Magdalena and La Guajira. These clones come to farmers through technological packets that include the use of agro-chemicals and fertilizes that modify regions’ natural ecosystems. In addition to this is the damage done to biodiversity when farmers, attempting to secure the sale of their produce, only plant one type of seed.

But this is only a small part of the road travelled by industrial cacao to arrive on our tables. This story is not only about a product with cloned seeds but also about a selection of beans which lacks rigour. In industrial processes which prioritise quantity over quality, varieties are mixed without qualm when they are collected. Once the beans have been fermented for several days and then dried, they are moved to the roaster without taking account of their different sizes. The small beans are burnt, the big ones are not roasted enough and thus, they are ground together to make the same paste or base. The low quality beans or husks which are thrown out during artisanal processing, are kept during industrial processing. And at this point, already far removed from the original flavor and aroma of the fruit, the uncountable preservatives and flavourings of an industry which appears generous and diverse (light chocolate, instant, vanilla flavoured, cloves and cinnamon…) are added. It is worth asking oneself how much cacao there actually is in the chocolate we are purchasing.

There are also innumerable details in the story of recuperating a seed. Let’s stop beating about the bush and come back to white cacao. Has it survived because of its lack of commercial importance to the national chocolate industry? Has it survived by being part of the diet of indigenous families who have prepared it in their houses in the middle of the Sierra for years? It is possible. Malanga, guatila, and chachafruto are other examples of native fruits that have no commercial importance, but which are nevertheless a high quality source of nutrition. What is not named is forgotten, and often it is someone from outside who makes us look inside and value what we have neglected.

More than three years have passed since APOMD and Slow Food first met in Dibulla. For Yarido Banquez, vice-president of the association, this process has not only meant the rescuing of the seed but also traditional forms of cultivation. This includes practices such as making organic fertilizer from what the surroundings provide, paying attention to the phases of the moon, varying crops and planting in triangles to protect the land, in other words: a type of agriculture which observes and applies what Nature itself has done for centuries. Beyond the difficulties caused by the lack of water caused by the El Niño phenomenon, the most difficult thing, according to Yarido, is to spread faith amongst other growers. The disappointing results of past State and private initiatives have created disbelief amongst farmers, and it is not easy to convince them to commit to a process which requires time and perseverance.

These cacao producers plant without knowing whether they will harvest any rewards, the Sierra has taught them that a lot can happen in eighteen months. For them, a clear way of building peace in Colombia is to take up the knowledge passed on from their ancestors, some of whom were Arhuaco indigenous people. Today, they are farmers who are aware of the harmful effects of the Green Revolution, and that is why they are trying to stand up to an economy which enslaves them and which generates food by poisoning the countryside. This is why they consciously choose the seed, as it represents their intention to free themselves and to free the land.

Daniel Carei, Fernando Oliveros y Yarido Banquez. Porcelana cacao producers.

Images and words by Crista Castellanos. A project financed by Slow Food International and IFAD.

Video commissioned by the NGO Habitat for Humanity, Colombia. 2014. Produced in Ciudadela Sucre, Soacha, Cundinamarca.

Quinua y Amaranto, a vegetarian restaurant in the La Candelaria neighbourhood of Bogotá, offers much more than just good products and good food. A chat with Magdalena Barón, who has managed this project for more than eight years, generates ideas, words, and questions. The tranquility and thoughtfulness with which she speaks are refreshing. Her short pauses reflect a women who has built, over time and life experience, a connection between herself and what she believes, what she does, offers, and consumes. Remembering her while I write, I have the feeling of having spoken with someone who wants to be consistent in what she thinks and feels in her heart.

Without really knowing her, I’m just writing personal impressions here, and probably risk boring readers who like objective writing. But faced with the need for proof or justifications, all I can say is that the coherence she communicates is reflected in the work she does with the other women in Quinua y Amaranto every day. Work which is seen, smelt, and tasted at lunchtime, in a single menu consisting of a soup, main dish, juice, and dessert: a vegetarian corrientazo (basic meal) which has nothing basic or common about it. Flavours, smells and colours, juices, salads, sweets and cereals which, despite being from our continent, are largely unknown to us. Fruits, seeds and roots which we don’t use at home, which we don’t grow, whose smell we don’t know, and whose colour and shape we can’t even imagine. Our high-speed cooking limits us, and curiosity about ourselves falls asleep.

As well as telling us about quinoa and amaranth, the star products of the restaurant, Magdalena also talked about guatila, a food which is scorned as the “poor-person’s potato,” in the same way in which chicha was also looked down on for its supposed power to stupefy. She told us about mamay and arazá, amongst many more fruits and products which are a whole story in themselves, seeds of other items.

Beyond letting people know about a fruit or cereal known, this shop invites us to re-view everything that we are. It invites us to re-discover and value the forgotten as a key act in consuming, buying, cooking, and eating. It’s not simply about a vegetarian restaurant, it’s a place with a caring approach to work and commerce which questions our consumption habits. In a world where progress is synonymous with untiring machinery, speed, economic growth, and purchasing power, finding people that know and trust small-scale producers, offer a good quality product, without hurry, and small-scale, is always a nice surprise. Magdalena doesn’t sacrifice quality for quantity. For her, the success or progress of a business is not measured in franchises or in large-scale production, rather in constant evolution which doesn’t override principles, philosophy or the way in which life itself is lived and dreamed.

In Quinua y Amaranto, the variety is not in a menu full of different dishes, but rather in the particularity of the ingredients which are used and the way in which they are prepared. Vegetables, empanadas, condiments, biscuits, cereals, fruits, infusions, artisanal cheeses, products as far as possible organic. The importance of knowing the value of what’s on offer and that every project, whether it’s commercial or not, has a direction and clear guidelines so as not to sacrifice, in the name of progress, what they believe.

The person you see in the photo is Astro. To tell the story of her life, you have to name regions at the extremes and frontiers of Colombian geography. A visitor from towns eight days away from Bogotá, she has got to know plants, resins, fibres, fruits, seeds and all kinds of materials that are used every day in indigenous communities. Objects, forms, and uses that lose validity. Creations which disappear with the arrival of new utilities, the majority from the plastics industry.

This is how the sieve the grandmothers used to use to strain juice or sift flour was replaced by a strainer. If you are lucky enough to have one of those grandmothers who holds on to everything, you might still find close to you artisanal materials and instruments that open the door to the past, to a memory which is also yours. So, you ask yourself things that enrich your world and your vocabulary: What is this object called? What’s it for? What’s it made of? Who made it and where?

Maybe this is the great power of craftwork: to generate questions. Hand-made objects which come into our lives and invite us to ask ourselves about their creators. Tikuna woodworkers, Piaroa weavers, Sikuani potters. Colombians like us. Close neighbours of a nature which is generous in materials which we know but rarely name: Chiquichiqui or Piassava fiber palm, Moriche palm, piragua reed, the woody grass yaré, and even the Bloodwood tree. So objects talk. Their presence questions sharp observers, attracts awakened senses and, beyond pure decoration, affirm that the unknown is not that far away; sometimes it is hidden, forgotten, in family cupboards and drawers.

Astro’s eyes have looked across landscapes that many of us have only seen in photos. Her hands have touched fibres, resins, and materials which one day not long from now will be watched over by the museum’s famous “do not touch” signs. A professional in textiles, and temporary member of organizations such as the Fundación Etnollano, the Fundación Zio-A’i, the Mayor’s Office of Inírida and Artesanías de Colombia; she has woven through her professional experience connections and friendships with artisans from regions like the Amazon and the Orinoco. Today, she developes her a own project, sharing knowledge and unique objects through Amahia, in Tibasosa, Boyaca.

The objects which you see on this page are a small sample of her travels and meetings. Pimpinas, stoves, baskets, bags which cut through her personal history and which arrive in Bogotá full of stories. Traditions and beliefs which make the invisible visible, and name out of silence that which most of us omit. Stories which get lost or which get left behind like maternal surnames. In Astro’s case – a singular case – this surname clarifies her spirit and reinforces her special nickname: Fagua, which in Muisca means star, guide between possible paths.